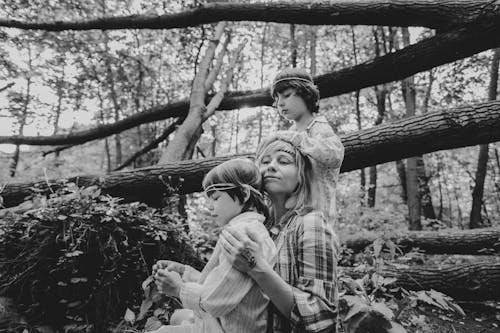

A robotic baby made an unexpected guest appearance on the runway at the Schiaparelli Couture Show in Paris earlier this year. Maggie Maurer, who had walked the runway pregnant in previous seasons and shared a photo of herself breastfeeding behind the scenes last year, cradled the infant while wearing a decidedly baby-unfriendly, all-white outfit.

It was a surprisingly tender moment. “I had the opportunity to bring it to life because my own child is this size,” says Maurer, “nurturing it… felt very natural.”

While this baby made of Swarovski crystals, flip phones, and other electronic debris made its debut, real babies were also seen on the runway this season, both in utero and out. At the highly anticipated show by French designer Marine Serre, a model wore a baby in a carrier adorned with the label’s crescent moon. At the quirky New York brand Collina Strada, a model walked the runway at 32 weeks pregnant.

But for some fashion professionals, the sight of babies on the runway might “sting,” says Natassa Stamouli, digital editor at 1 Granary. The leading global fashion education platform and creative network recently released new research showing how difficult it is to be a mother in the industry. They surveyed female designers and found that the majority cited lack of support for motherhood as a prominent example of gender discrimination in the fashion industry.

“We talked to chief designers in luxury houses who hide the fact that they have children, fearing they may not appear ‘committed enough’,” says Stamouli. “We heard many stories of HR departments rejecting a qualified candidate because their ‘motherhood could distract them’.”

Stamouli sums up the industry’s attitude: “In luxury design studios, being or wanting to be a parent, particularly mothers, is seen as a threat to the only acceptable work profile: the ultimately devoted professional whose life is fashion.”

Maurer found her experience of being a mother in the industry “incredibly liberating and incredibly supportive.” But she points out that it’s probably because she’s a model. “I only work for one day; when you’re a designer, you’re working in a job that requires going to the office every day. Every designer I’ve ever worked with is a workaholic because that’s what the industry demands.”

Stamouli says these expectations extend beyond top positions: “In styling, writing, and at independent brands, freelancing has become the norm, leading fashion professionals into a dead end of instability and financial insecurity. Getting pregnant, going on a fertility journey, taking maternity leave, and becoming a mother require free time, a peaceful mental state, and some financial stability. Most fashion jobs cannot offer any of that.”

The research resonates with sustainable fashion designer and mother of two Amy Powney, who runs her own label, Mother of Pearl. Once, she reached out to a headhunter who wanted to know her next steps. “Midway through, I said, ‘I just want to reiterate, if an opportunity were to come up, my children come first and I won’t change that.’ The tone of the conversation changed after that.”

She believes there’s an expectation that “if you want to become creative director of a major brand, you just have to do the job, that’s it. I don’t think there’s a conversation about how you could be supported and be a mother and have flexibility.”

It’s a shame, says Aya Noël, print editor at 1 Granary, “because many of the mothers we spoke to say that after having their children, they’ve become better employees and creatives. They manage time more efficiently or have more patience or empathy. Our industry shouldn’t miss out on these skills just because we have an old-fashioned mindset in the way we structure the studio.”

There are exceptions. Phoebe Philo is famous for being the first designer to take maternity leave while creative director of a luxury fashion house. However, shortly after, she left her job at Chloé to raise her family for four years. This season, designers Molly Goddard and Chloé’s new creative director, Chemena Kamali, made special efforts to wave to their young children as they took bows after their shows – proving that juggling is possible for some.

Philo is often celebrated as a powerful example of a woman designing clothes for women, while male designers sometimes miss the mark. If the industry wants to retain this talent, it seems sensible to better align the system to support parents.

There’s another point here, too. This fashion moment for motherhood coincides with a worsening gender pay gap. According to figures released last week, British mothers earned £4.44 less per hour than fathers in 2023.

“It’s interesting that runways glamorize the fantasy of ‘baby mama chic’ while birth rates among Western women are plummeting,” says fashion and identity commentator Caryn Franklin. “Our gendered work landscape…

Discussion about this post